The Impact of the Extension of the Pedestrian Zone in the Centre of Brussels on Mobility, Accessibility and Public Space

Résumé. Depuis 2015, la zone piétonne bruxelloise s’étend le long du boulevard Anspach. Quel impact cela a-t-il sur les pratiques de mobilité et les raisons de la visite, sur la satisfaction en termes d’’accessibilité du centre-ville et sur la qualité de l’espace public? Bruxelles Mobilité (Région de Bruxelles-Capitale) a chargé la VUB-MOBI et le BSI-BCO d’aborder ces questions par le biais d’une enquête de suivi à grande échelle, avant et après les réaménagements. Les résidents de la zone métropolitaine (BMA), les employés ayant un emploi dans le centre-ville et les visiteurs de la nouvelle zone piétonne ont été interrogés. Cette contribution présente les résultats les plus importants obtenus auprès des 4870 répondants de la première enquête (avant redéploiement). Une analyse plus détaillée sera disponible dans l’étude complète (à paraître, VUB MOBI – BSI BCO et Bruxelles Mobilité). Nous soulignons, qu’en général, la majorité des répondants étaient en faveur d’un boulevard Anspach piéton plutôt que contre. La plupart des visiteurs se rendent dans la nouvelle zone piétonne à des fins de loisirs. La plupart des visiteurs se rendent régulièrement dans le centre-ville, en particulier les résidents du centre-ville et ceux habitant les autres communes de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale. En termes d’appréciation de l’espace public, les visiteurs indiquent que les points le moins satisfaisants sont la propreté de l’espace public et leur sentiment de sécurité de jour comme de nuit. En outre, 36% des habitants de la région métropolitaine (BMA) interrogés ont déclaré que la zone piétonne affectait leur choix de mode de transport lorsqu’ils se rendaient vers et dans le centre-ville. Beaucoup d’entre eux ont indiqué qu’ils ont utilisé les transports en commun plus souvent qu’avant. Enfin, les auteurs proposent des recommandations pour améliorer le piétonnier, sur base des résultats de l’enquête.

Abstract. Since 2015, the Brussels pedestrian zone has been extended along boulevard Anspach. What impact did this have on travel and visiting behaviour, the perceived accessibility of the centre, and the quality of its public space? Brussel Mobiliteit (Brussels Capital Region) commissioned a large-scale follow-up survey to VUB-MOBI & the BSI-BCO to answer this question and monitor the effects before and after the renewal works. Brussels Metropolitan Area (BMA) inhabitants, city-centre employees and pedestrian zone visitors were questioned. This paper presents the most important findings from the 4870 respondents of the pre-renewal survey. A more detailed analysis will be available in the full research report (forthcoming, VUB-MOBI – BSI-BCO & Brussel-Mobiliteit). In general, more respondents were in support of a car-free Blvd Anspach than against it. Most visitors go to the new pedestrian zone for leisure-related purposes. Overall, the users are also mostly regular visitors, including inhabitants of the city centre and other Brussels inhabitants. In terms of appreciation of public space, the most problematic aspects are cleanliness and safety concerns whether during the day or by night. Furthermore, 36% of the BMA respondents stated that the closure for cars has influenced their choice of transport when going to the city-centre. Many of them use public transport more often. Lastly, the authors put forward recommendations to improve the pedestrian zone considering the survey’s results.

Original Research

Imre Keserü, Mareile Wiegmann, Sofie Vermeulen, Geert te Boveldt, Ewoud Heyndels & Cathy Macharis

VUB-MOBI – BSI-BCO

3.1. Characteristics of visits to the city centre and the pedestrian zone

3.2. Influence of the introduction of the pedestrian zone on the travel behavior of visitors

3.4. Change in perception of the accessibility of the city centre

3.5. Support for a car-free Blvd Anspach

3.6. Perception of the public space of the newly pedestrianized area

4.1. Integrate metropolitan users in the appropriation of the city centre

4.2. Provide clear information and affordable transport alternatives to car-users

4.3. Improve the information and access to the city centre for bus-users

4.4. Install attractive and temporary urban furniture and program activities in public space

1.Introduction

On 29 June 2015 boulevard Anspach (Blvd Anspach) and several adjacent streets (the central boulevards) were closed for motorised traffic as part of the plan to extend the pedestrian area in the centre of Brussels. Due to the lack of a comprehensive monitoring scheme, many stakeholders have questioned the credibility and accuracy of the data published regarding the impact of the scheme, referred to as “the piétonnier” [Keserü et al., 2016; Vanhellemont and Vermeulen, 2016]. Since mobility was one of the most controversial areas of impact and data was unavailable to confirm the different claims about those impacts, a large-scale survey has been commissioned by the Cabinet of the Minister for Mobility and Public Works and Brussels Mobility to monitor the impact of the pedestrianisation project on travel behaviour and the appreciation of the new pedestrian area.

The survey aims to provide a comprehensive monitoring of the impact of the Brussels pedestrian zone on the travel behaviour of users of the area and how they perceive and appreciate the accessibility of the area, the functioning and design of the public space and the built environment. The following research questions have been addressed:

- What is the current travel behaviour of the Brussels Metropolitan Area (BMA) inhabitants, the employees of the city centre and the visitors of the city centre and the central boulevards who use the pedestrianised area?

- How has the travel behaviour and modal choice of visitors of the city centre and the pedestrian zone been influenced by the introduction of the pedestrianised area (in combination with changes in public transport and parking facilities)?

- What is the visitors’ degree of satisfaction with regards to accessibility of the Brussels city centre and the newly pedestrianised area?

- How has the perception of the accessibility of the city centre changed?

- What is their perception of the interventions in the public space of the newly pedestrianised area?

- How has the perception of the public space of the newly pedestrianised area changed?

- How do the above variables vary according to different socio-demographic variables and place of residence?

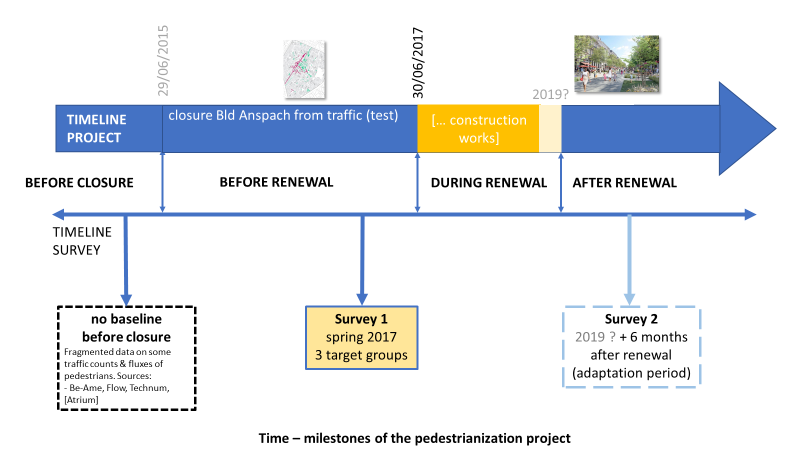

To answer these research questions, a longitudinal survey has been set up with two survey moments. The first one was carried out in spring 2017 and a second one will be organised 6 months after the construction works are completed (estimated in 2019). Since no baseline survey was conducted before the new traffic circulation plan came into effect in June 2015, there is only fragmented data available on the situation before the extension of the pedestrian zone. This survey aims to overcome this problem by asking respondents not only about their current behaviour and opinions, but by also making a comparison with the situation prior to the pedestrianisation (retrospective survey) (figure 1).

Figure 1: Milestones of the pedestrianisation project and the surveys

The survey focuses on three target groups (T1, T2 & T3) representing the usersof the new pedestrian zone:

- T1: Residents of the Brussels Metropolitan Area (BMA)[1], i.e. “metropolitan residents”

- T2: Employees working at a company or other organisation that is located in or near the pedestrian zone; i.e. within the Pentagon irrespective of their residential address; i.e. “employees in the city-centre”

- T3: Visitors of the ‘new’ pedestrian zone(i.e. boulevard Anspach and some adjacent streets which are located within the perimeter of the requested planning permissions of the extension of the pedestrianised areas), irrespective of their residential address, i.e. “visitors of the piétonnier/pedestrian zone”

The aim of this paper is to outline the most important findings of the first survey that took place in Spring 2017. The detailed analysis will be available in the full report.

2. Method

The three target groups were approached by different survey methods (seeTable 1for a summary). The metropolitan residents (T1) and the employees working within the city centre – i.e. the Pentagon (T2) were surveyed through an online questionnaire, while the visitors of the new pedestrian zone in and around Blvd Anspach (T3) were surveyed through face-to-face interviews. The three surveys delivered 4870 responses in total. The three samples were analysed separately because they provide data about distinct subsamples of the visitors of the city centre of Brussels and the pedestrianised area.

3. Headline results

3.1. Characteristics of visits to the city centre and the pedestrian zone

The survey of the inhabitants of the Brussels Metropolitan Area (BMA) made it possible to reach persons who have not visited the city centre since 2015 and ask them about their reasons for not visiting.

10.3% of the metropolitan inhabitants reported they had not visited the centre of Brussels before boulevard Anspach was made car-free in July 2015. The proportion of non-visitors is higher among residents who live further away from the city centre: 6.9% of people living outside the city centre (Brussels 1000) but within the Brussels Capital Region, and 17.5% of respondents living outside of the Capital Region stated that they had not visited the centre since July 2015.

In addition, 14.6% of those who visited the city centre since July 2015 did not go to the extended pedestrian zone at the central boulevards (Blvd. Anspach). In other words, 24.9% of the BMA inhabitants surveyed have not seen the new pedestrian zone.

Most of the respondents in the samples of BMA residents (T1) and visitors of Blvd. Anspach (T3) mainly visit the city centre for a leisure-related purpose. Leisure shopping, visiting bars and restaurants, taking a stroll and attending social & cultural activities were mentioned as the most important reasons. Leisure shopping was by far mentioned by the largest proportion of respondents living in the BMA (T1) as their main purpose (27% of the visitors from the BMA).

Table 1: Target groups and survey methods

| SURVEY | T1 | T2 | T3 |

GROUP OF RESPONDENTS |

Inhabitants that (no longer) visit the Brussels City Centre and the pedestrian zone aged 18 and over |

Employees working in the Brussels City Centre aged between 18 and 64 | Visitors of the new pedestrian zone within the Brussels City Centre aged 18 and over |

| TYPE OF QUESTIONNAIRE | Online questionnaire (CAWI) | Online questionnaire (CAWI) | Face-to-face interviews in the street (CAPI) |

| SELECTION OF RESPONDENTS | Online panel | 2-step sampling | Intercept survey – on street at 5 locations between 8-22h during weekdays and weekend |

| AREA OF SAMPLING | Brussels Metropolitan Area

Place of residence in one of 19 municipalities BCR or one of 33 municipalities (1st Brussels’ periphery). [cf. area Iris 1-plan Brussels Capital Region, 1997; Lebrun et al, 2012]. |

The Brussels City Centre – ‘Pentagon’

Employees within the Pentagon, regardless their place of residence. |

“The piétonnier”

People present at one place on the Central boulevards at 5 locations: 1) place de Brouckère 2) boulevard Anspach 3) place de la Bourse 4) place Fontainas 5) rue A. Orts |

| LANGUAGE | FR / NL | FR / NL / EN | FR / NL / EN |

| SURVEY PERIOD | 17/05/2017-06/06/2017 | 06/06/2017-11/07/2017 | 02/05/2017-22/05/2017 |

| REALISED SAMPLE SIZE &

PLANNED SAMPLE SIZE |

N = 1007

(target : n=1000) |

N= 2406 (target : n = 800) |

N = 1457

(target: n = 1400) |

For the visitors that were intercepted on Blvd Anspach (T3) the main purpose of visit was taking a stroll or ride for leisure (31%) followed by leisure shopping (21%). This indicates that the most important attraction of the city centre is the large variety of shopping opportunities, but for the actual visitors of Blvd. Anspach, taking a walk is the primary purpose, which may refer to the appeal of the new pedestrian area as a living and meeting place. Among the employeesof the city centre (T2), the most important ‘other’ purpose respondents mentioned as activities they combine their usual trip to work with was leisure shoppingmentioned by 71% of the respondents.

Our data on visitors (T3) shows that Blvd Anspach is intensively used by the residents of the Brussels Capital Region (BCR) (62% of all respondents)and especially those living in the city centre (26 % of all respondents).At the same time, the share of visitors from the 1stperiphery (Rand) is relatively small (5%). At the same time, there is a high number of foreigners present in the pedestrian zone: over one-fifth (22%) of the visitors live abroad, affirming the touristic appeal of the city centre. Generally, this shows that the users of the pedestrian zone are mostly regular visitors, including inhabitants of the city centre and other BCR inhabitants.

While the residents of the Brussels Metropolitan Area (T1) and the employees in the Pentagon (T2) were asked to indicate their usual transport mode to access the centre of Brussels(the area within the Pentagon), the visitors of Blvd Anspach were also asked about their current trip, i.e. the trip that includes visiting the newly pedestrianised area itself (Blvd Anspach) as they were interviewed there.

All three surveys confirm that the main mode of transport to access the city centre is public transport. 60% of the BMA residents (T1) and 61.3% of the employees working in the Pentagon (T2) take the train, bus, tram or metro when travelling to the centre. This is followed by the car (27% of BMA residents and 24% of employees in the Pentagon). When looking specifically at the travel mode of visitors to access Blvd Anspach (T3), the main mode is still public transport (54%) but walkingis the second most important with over one third (35%) of the visitors indicating it as their main mode. The proportion of those who travelled by car is very low (13%).

3.2. Influence of the introduction of the pedestrian zone on the travel behaviour of visitors

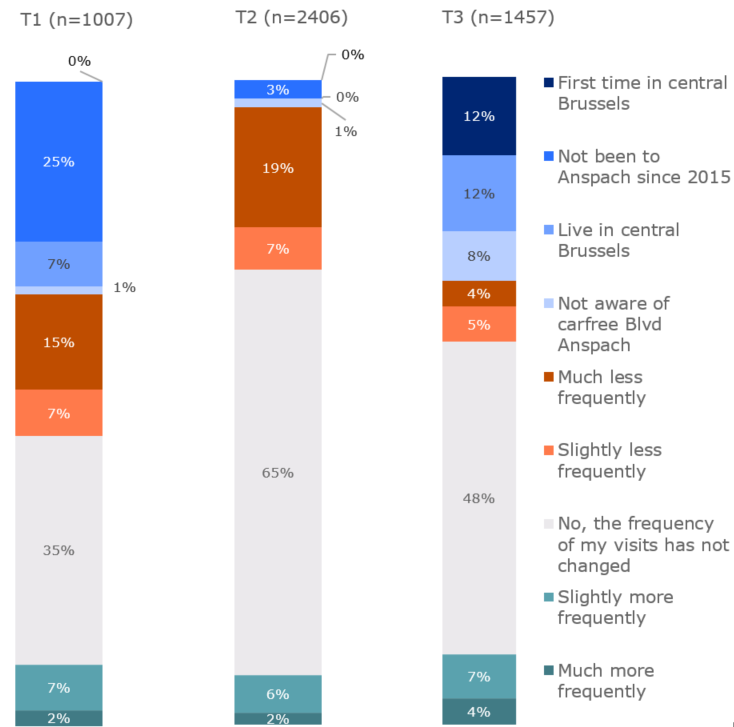

There is indication that among the residents of the BMA (T1) and employees in the Pentagon (T2) those who still visit the pedestrian zone do it less frequently. Both for the residents of the BMA and the employees working in the Pentagon there are significantly more respondents, who stated that they visit the centre less often due to the changes around Blvd Anspach than those who go more often (Error! Reference source not found.). Amongst those interviewed on Blvd Anspach (T3), however, those visiting more often outweigh those coming less often.

The main reasons for visiting less frequentlyare the deterioration of accessibility, unattractive environment, the worsening of subjective security and parking difficulties. The main reasons for going more oftenare the more attractive environment, better accessibility, and the interesting activities and events. These results indicate a difference between two groups: people living outside Brussels generally visit the city centre less than before, while those living in the BCR report they visit the car-free Blvd Anspach more than before.

There are slightly more people in T1 who said that they stay in the city centre for a shorter duration since the closure of Blvd Anspach for car traffic than those who stay longer. Only the inhabitants of the centre (postcode 1000) had a majority of those stating that they stay longer. Again, this affirms that the pedestrian zone is part of a paradigm shift to better liveability for local residentsin the first place, which is in line with the impact of other pedestrianization schemes [Hass-Klau, 1990; Gehl, 2011; Boussauw, 2016].

The responses indicate a potentially significant change in the mode choice of those visiting the city centre. More than one third (36% of the respondents) living in the Brussels Metropolitan Area (T1) declared that the removal of car traffic from Blvd Anspach had an influence on their choice of transport. For the people employed within the Pentagon (T2), almost one in five of the respondents (18%) changed travel mode for commuting. Among the visitors of Blvd Anspach (T3), 20% stated they made changes to their choice of transport.

The most significant change is an increased preference for public transportas opposed to the car in all three samples. The share of respondents who stated that they visit the centre less by car and more by public transport is 15% (T1), 9% (T2) and 7% (T3) (percentages based on share amongst those who have been to the centre both before and after July 2015 and do not live in the city centre) indicating a potential shift in modal choice from car to public transport.

Approximately as many respondents stated that they use active modes (cycling and walking) more as those that stated using them less among the metropolitan residents (T1). There is a net shift towards active modes for employees (T2: 7.6% come more and 2.4% state to come less) and visitors (T3: 8.2% more and 2.3% less) of Blvd Anspach.

3.3. Degree of satisfaction with the accessibility of the centre of Brussels and the newly pedestrianised area

Those who usually drive to the city centre have the most negative opinion about the accessibility of the centre. The problems they mentioned most are time lost in traffic jams and lack of parking places. 59% of the respondents in T1 and 64% in T3 needs more than 6 minutes to find a parking place.

In contrast, forthose who travel to the centre mostly by public transport, the satisfaction with the accessibility by public transport is quite positive. Especially regarding travel time/connection, they are mostly satisfied with the current situation. A lower level of satisfaction with information about the offer of public transport indicates the need for improvement in this area.

3.4. Changes in perception of the accessibility of the city centre

Car drivers have the perception that the accessibility of the city centre generally became worse. This is manifested in a large proportion of respondents who drive to the city centre stating that they find reaching their destinations, the fluidity of traffic, finding available parking places more difficult or worse than before the closure of Blvd Anspach for car traffic. This may point to the unclear traffic signalisation, the delayed adaptation of Satnav maps, lack of P-routing and the inadequate communication about the accessibility of the city centre in general.

Public transport users however, experienced little change in accessibilitywith the majority (at least 60%) in all three samples experiencing no change. At the same time approximately as many people perceived an improvement in accessibility, while a similar same share reports a deterioration in accessibility. When asking more regular users, employees (T2) and visitors to Blvd Anspach (T3), the location of bus stops and information about public transport around Blvd Anspach were more often judged negatively than positively.

3.5. Support for a car-free Blvd Anspach

There is quite a variation in the level of support for a car-free Blvd Anspachacross the types of visitors but overall the proportion of supporters exceeds the percentage of non-supporters in all three samples. In the sample of the BMA (T1), there are more respondents in favour of the car-free Blvd Anspach (47%) than against (31%). Those who visit Blvd Anspach regularlyi.e. employees in the city centre (T2) and the visitors of Blvd Anspach (T3) are more in favour of the car-free Blvd Anspachthan the general BMA population with visitors interviewed on Blvd Anspach (T3) having the highest proportion of approval (69% vs. 20% of disapproval).

Visitors from abroadinterviewed on and around Blvd Anspach (T3) have a significantlyhigher supportwith 80% of them supporting a car-free Blvd Anspach, possibly because they are not aware of the controversial media coverage of the pedestrianisation scheme. Also, because they are mostly one-time visitors their opinion is formed by just a single impression – which is positive – as opposed to more frequent visitors or local and metropolitan residents.

Figure 2: Change of frequency of visits after the removal of traffic from boulevard Anspach

3.6. Perception of the public space of the newly pedestrianised area

28% of the residents of the BMA (T1) who visited the city centre since July 2015 did not know about plans to further redevelop the area. Amongst employees surveyed (T2), 25% were also not aware. Among the visitors (with many tourists amongst them) (T3), 19% did not know it had been made carfree recently and 44% did not know about the upcoming refurbishment.People who visit the centre more frequently and live closer to the centre are more aware of the planned redevelopment: roughly only half of the people living in the Brussels periphery (T1 subsample) know about the redevelopment.

When asked about the current state of Blvd Anspach, a generally negative picture arises. Across the aspects of cleanliness, comfort, atmosphereand safety, residents of the BMA (T1) and employees working in the centre (T2) had mostly negative impressions. Actual visitors to Blvd Anspach (T3) have a slightly better image. The two statements receiving the highest negative assessment are perceived dirtinessboth day and nightand the problems with personal safety during the night.

More than half of the respondents from the BMA (T1) try not to visit Blvd Anspach after dark to avoid being bothered. This proportion is only slightly smaller among the actual visitors of Blvd Anspach (T3) indicating a high degree of negative perceptions about safety. Slightly more than a quarter of respondents actually visiting Blvd Anspach (T3)try toavoid it even during the day to avoid being bothered.

There is mostly overall agreement of the good availability and appeal of restaurants, bars and shops, as well the appealing character of streets and facadesand the comfort of the street surfacein the pedestrian area in all three samples. When it comes to further design aspects of public space, most respondents donot find enough places to sit and do not find enough greenery. Lack of information about the upcoming works was also mentioned by at least one third of the respondents (38% in T1; 56% in T2; 57% in T3).

Based on data from all three target groups, the pedestrian zone is perceived to have gotten worse in three aspects: cleanliness of the street and safety from harassment both at night and during the day. However, in terms of public space, the majority of respondents stated that the zone has improved with more possibilities to sit down, increased comfort of walking surface and presence of some greenery.This may indicate a general appreciationof more street surface dedicated to pedestrians and the presence or higher visibility of temporary urban furniture. These results cannot point to the renewed public space as construction works are still in progress.

The appreciation of the type of shops and restaurants is perceived to have stayed about the same before and after the closure of Blvd Anspach for traffic. On the one hand, this affirms a general appreciation of the offered diversity of shops and services located in the city centre [Decroly & Wayens, 2016; Boussauw, 2016]. On the other hand, this may indicatethat visitors of the pedestrian zone do not experience the increased failure of certain types of economic activities (daily groceries, some niche products…) even though complaints of local entrepreneurs have been dominant in (local) public debate.

4. Recommendations

Based on the results of the survey we make the following four recommendations:

4.1. Integrate metropolitan users in the appropriation of the city centre

The closure of Blvd Anspach seems to have had the greatest impact on people living within the Brussels periphery in terms of reducing the number and frequency of visits. Also, these people are the least supportive of the mobility measures of the entire project and represent a large proportion of those travelling to the centre by car. Therefore, we recommend that people living outside the BCR but potentially visiting the pedestrian area should receive better information about the redevelopment of Blvd Anspach and the alternative transport options (public transport, train, Park and Ride).

At the same time, the ‘image’ of the pedestrian area could be improved within this group with a temporary refurbishment of public space (a sort of alternative preview on how the new area will look like) and a comprehensive communication policy providing basic information about the content, progress, expected consequences on accessibility of the entire project and activities taking place in the city centre. This is not only relevant once the currently ongoing works have finished. Visitors that are informed about eventual nuisance digest them better and visitors that experience a high quality temporary space are more likely to appropriate that space in a positive way. Such a communication policy should also target people who do not visit the city centre any more due to accessibility or safety concerns.

4.2. Provide clear information and affordable transport alternatives to car-users

People who access the city centre by car seem to have the most negative perception of the impact of the pedestrianisation scheme. Therefore, a targeted information campaign should inform them about alternatives to access the city centre e.g. the advantages of Park and Ride. P-routes must also still be improved. Joint campaigns with retailers (e.g. providing free public transport to/from a Park and Ride when making purchases in the centre or visiting certain bars or restaurants) could improve the image of the pedestrian area and promote the use of sustainable modes to access it.

4.3. Improve the information and access to the city centre for bus-users

While public transport passengers have a higher level of satisfaction of accessibility, there are some aspects that need improvement. The location of the bus stops and information about public transport in and around Blvd Anspach should be improved. This is in line with a general recommendation to develop a communication policy for the entire project [Hubert, Corijn, Neuwels, Hardy, Vermeulen, 2017].

4.4. Install attractive and temporary urban furniture and program activities in public space

The attractiveness of Blvd Anspach and its future success depends on several factors that were highlighted by the respondents:

- improvements of the built elements of the public space (new pavement, street furniture, greenery);

- continuous maintenance of the physical infrastructure (repairs, cleaning);

- and a better perception of safety during day and night (alternative activities).

This largely corresponds to the recommendations made earlier by the BSI-BCO [Hubert et al.,2018]. The proposals on a ludic art parcours, the strategic programming of activities in public space made by the initative ]pyblik[ can easily be implemented to improve the overall appreciation of the area (see Kums & Van Dooselaere in this Portfolio).

5. Limitations of the study

The results have some limitations. Through these surveys it was not possible to determine the exact modal split (measured by number of trips or passenger-kilometres) for two reasons. On the one hand we did not have information about the exact number of trips the respondents make and the length of the trips. In order to collect such data a different approach would have been required using a travel diary to register all trips and length of trips on specific days. The travel diary approach would have increased the length of the questionnaire considerably leading to a higher rate of respondent dropout or non-response and limited opportunities to ask further questions about perceptions and changes in perceptions. On the other hand there was no baseline survey carried out before the closure of Blvd Anspach to identify travel behaviour before the pedestrianisation scheme started. Carrying out a detailed survey of travel behaviour including number and length of trips almost two years after the baseline period (before July 2015) would have been unrealistic as respondents would not have been able to remember their exact behaviour.

When attempting to approximate shifts in the use of transport modes across the population, we cannot without doubt define a respondent’s past main mode of travel. So we assumed that if a certain travel mode was used more in the past, it was the main travel mode back then.

Perceptions about the pedestrianisation scheme, Blvd Anspach and the city centre in general may have been affected by the terrorist attacks in Brussels on March 22, 2016 and to a lesser extent the lock-down after the attacks in Paris on November 13, 2015. Therefore, perceptions about the attractiveness and especially the safety of the city centre and Blvd Anspach may not necessarily only reflect the impact of the pedestrianisation project but also this more general context.

Also, the overwhelmingly negative perceptions about accessibility of the city centre by car, congestion and parking may not be solely related to the closure of Blvd Anspach but to the generally high level of congestion of roads and parking difficulties within the Pentagon, the inadequate communication about the whole project and the circulation plan in particular and a number of other renewal projects in the Pentagon (e.g. Porte de Ninove, renewal of the tunnels). But the contrast with the satisfaction of the public transport users must also be underlined.

[1]The Brussels Metropolitan Area includes the 19 municipalities within the Brussels Capital Region (BCR) and 33 surrounding municipalities[1], i.e. the first Brussels periphery (‘de eerste rand’) as defined by the IRIS-1 regional mobility plan [Brussels Capital Region, 1997]: Grimbergen, Vilvoorde, Machelen, Steenokkerzeel, Zaventem, Kortenberg, Kraainem, Wezenbeek-Oppem, Tervuren, Bertem, Overijse, Huldenberg, Hoeilaart, St Genesius-Rode, Linkebeek, Beersel, Drogenbos, Halle, Sint-Pieters-leeuw, Lennik, Dilbeek, Ternat, Asse, Merchtem, Wemmel, Meise, Braine-le-Château, Ittre, Braine-l’Alleud, Waterloo, Lasne, La Hulpe, Rixensart.

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to thank all people who have contributed to this research in one way or another: the cabinet of the Brussels Minister for Mobility and Public Works Pascal Smet, Brussel Mobiliteit, Stad Brussel, VAB, Atrium, Algemene Directie Statistiek – Statistics Belgium, BISA, Fédération Horeca Bruxelles, RAB-BKO, perspective.brussels, Sociare, de Verenigde Verenigingen, MIVB-STIB, BPOST, Federale Politie, VGC, Odisee, Unizo, UCM, BECI, TNS Kantar, the different HR-departments who distributed the survey amongst employees, and last but not least, our colleagues at IGEAT (ULB), the team of CES (USL-B), and all people involved in the BSI-Brussels Centre Observatory. Special thanks to Raf Pauly and Daan Hubert.

References

BOUSSAUW, K., 2016. Lokale economische aspecten van voetgangersgebieden: een beknopt literatuuroverzicht. In : Corijn, E., Hubert, M., Neuwels, J., Vermeulen, S. & Hardy, M. (Eds.), Portfolio#1 : Cadrages – Kader, Ouvertures – Aanzet, Focus. (pp. 89-96).Bruxelles :BSI-Brussels Centre Observatory. Available at: https://bsi-bco.brussels/lokale-economische-aspecten-van-voetgangersgebieden-een-beknopt-literatuuroverzicht/

BRUSSELS CAPITAL REGION, 1997. IRIS-plan: Een gewestelijk vervoerplan voor het Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest.Brussels, Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest.

DECROLY, J.-M., & WAYENS, B., 2016. Le centre-ville : un espace multifonctionnel. In : Corijn, E., Hubert, M., Neuwels, J., Vermeulen, S. & Hardy, M. (Eds.), Portfolio#1 : Cadrages – Kader, Ouvertures – Aanzet, Focus. (pp. 21-34). Bruxelles : BSI-Brussels Centre Observatory. Available at:https://bsi-bco.brussels/le-centre-ville-un-espace-multifonctionnel/

GEHL, J.,2011.Life between buildings. Using public space. Washington DC: Island Press.

HASS-KLAU, C., 1990. The pedestrian and city traffic. London: Belhaven Press.

HUBERT, M., CORIJN, E., NEUWELS, J., HARDY, M., VERMEULEN, S. & VAESEN, J., 2017. Du « grand piétonnier » au projet urbain : atouts et défis pour le centre-ville de Bruxelles. Brussels Studies[Note de synthèse], no. 115, Available at: http://brussels.revues.org/1551. http://doir.org/10.4000/brussels.1563

KESERÜ, I., WUYTENS, N., DEGEUS, B., MACHARIS, C., HUBERT, M., ERMANS, T. & BRANDELEER, C., 2016, Monitoring the impact of pedestrianisation schemes on mobility and sustainability.Corijn, E., Hubert, M., Neuwels, J., Vermeulen, S. & Hardy, M. (Eds.), Portfolio#1 : Cadrages – Kader, Ouvertures – Aanzet, Focus. (pp. 97-115).Bruxelles : BSI-Brussels Centre Observatory. Available at:https://bsi-bco.brussels/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/BSI-BCO-P1-Keseru-etal.pdf

LEBRUN, K., HUBERT, M., DOBRUSZKES, F., HUYNEN, PH., 2012. Het vervoeraanbod in Brussel, Brussel. Katernen van het Kenniscentrum van de mobiliteit in het Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest, n° 1. Brussel : Brussel Mobiliteit. Available at: https://mobilite-mobiliteit.brussels/sites/default/files/katernen-kenniscentrum.pdf

VANHELLEMONT, L. met VERMEULEN, S., 2016. De aanleg van de voetgangerszone in het Brusselse stadscentrum (2012-…). Een analyse van (het discours van) het procesverloop. In: Corijn, E., Hubert, M., Neuwels, J., Vermeulen, S. & Hardy, M. (Eds.), Portfolio#1 : Cadrages – Kader, Ouvertures – Aanzet, Focus. (pp. 79-86).Bruxelles :BSI-Brussels Centre Observatory. Available at: https://bsi-bco.brussels/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/BSI-BCO-P1-Vanhellemont-Vermeulen.pdf

NL

NL FR

FR